01

a mocking yet thoughtful grin shimmers between his lines when the philosopher and sinologist françois jullien muses on how long european culture has matured, only to immediately question itself again with the greatest joy and to dismantle the foundations that have been laid for centuries. in his book ‚china and the psychoanalysis‘, the transition from the 19th to the 20th century is his reflected climax and the so-called critical mindset is the guarantee for the descent. at this time, colonized asia was slowly beginning to reshape itself, and the 1904 russo-japanese war, of all things, in which a great european power could be defeated by asians in modern times, inspired the young mahatma ghandi to ponder resistance, albeit a non-violent one. more than a century later, china and japan are back in their firmly rooted, historical boots, while the history-free european continent whimpers barefoot towards the coming tide.

02

for over two centuries, the tokugawa shogunate refined japanese culture in the edo period, which was based on absolute rules. society was strictly hierarchical, with class, family, the individual and art, literature, gardening, everyone and everything following a predetermined path that could never be abandoned. however much sumi-e, haiku and karesansui represent the highest precision in form and expression, they are at the same time the result of total state control, an order guaranteed by an implacable authority. in this fine-meshed regulatory structure, personal freedom can only be found in the niches, the small gaps, and thus the idea of MA develops, in which emptiness emerges as free space, as possibility, in contrast to the concept of emptiness in the west, which means a darkness borne of loss and mourning. this emptiness can also be found in the surface left free, the unpainted piece of paper, in which the contrast between form and non-form is questioned and beauty is sought in the balance of both elements. the emptiness becomes a connection, a play with time and displacement.

03

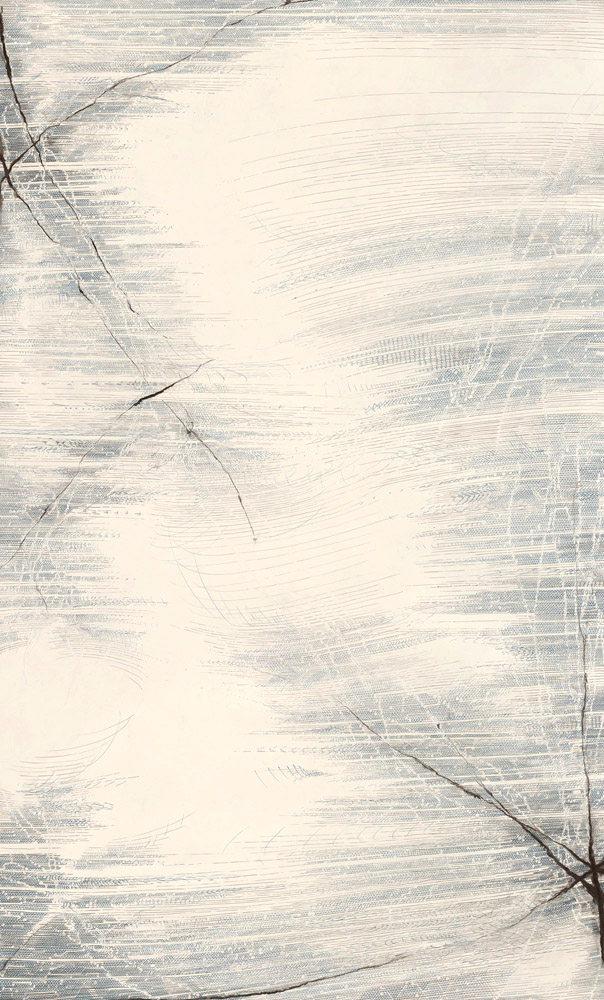

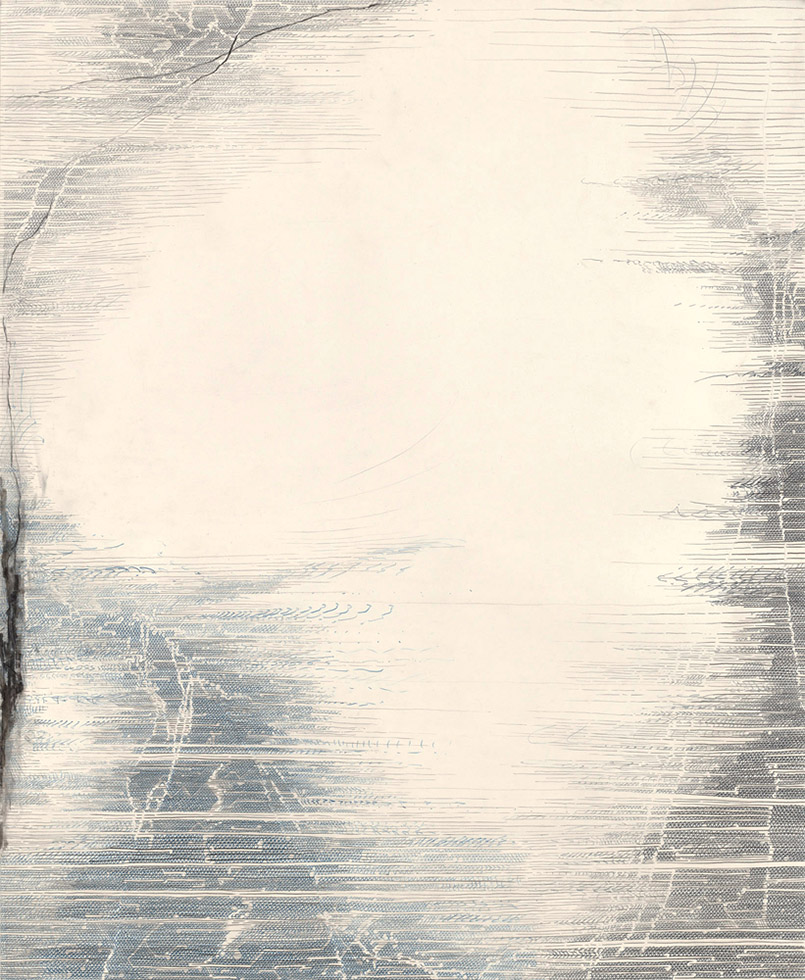

kazuki nakahara interfuses his white paper surface rhythmically and structurally, his traces of drawing, mostly applied with colored pencil on large sheets of japanese paper, conquer the empty space like water. prepared in conceptual sketches, these dancing fragments of typography flow around the white islands to be left free, only to be embraced and held by stronger charcoal lines spanning the sheet shortly before the work is completed. with the spatial distance in front of the work, in which drawing and painting merge, the hatching of the details loses its focus and gives way to a velvety overall picture that appears worn through frequent use. in accordance with another way of perceiving the world that stems from zen buddhism, nakahara’s art also envelops wabi sabi, the simple, impermanent. although these thoughtfully placed compositions play with impermanence, a temporal rift is created in the interaction of space and non-space, as something very old enters into a dialog with something very new and young.

04

the architect and visionary kengo kuma, known in the west not only for his contribution to the royal academy exhibition ’sensing spaces‘, describes in detail how he seeks the void in his architecture, the ma. the project, he says, is prosperous when he succeeds in creating a human, warm and natural space. with the japanese economy weakening after 1991, the architect’s commissions tended to remain regional. a lively collaboration with local craftsmen developed, providing kuma with a working basis for future buildings. the project ‚the exchange‘, which opened in sydney in 2019, clearly demonstrates the parallels to nakahara’s approach. a wooden band wrapped around the actual building disguises the form and function of the underlying architecture. the invisible space, concealed behind the deceptive surface of a playful reality, aware of its impermanence, opens the invitation to dance. with the suggestion of a figurative legibility, nakahara’s work is wrapped by the idea of opening this enticing, ajar door to step into the sun.

05

if it is the façade behind which we are supposed to look, the beach that calls out hidden beneath the concrete, the image we are looking at, that is, flips a switch in us in order to reach a different, hidden perception, we are either the victim of our insatiable restlessness, or we are willingly and calmly drifting along on the river of infinite change. nakahara is a master of the art of taking up space. in the play between proximity and distance, factual representation and abstraction, the artist oscillates between the drama of the real outside world and the inflammable journey into the inner self. whether we want to see transience in an abstract surface or sense the finely driven path systems of tunnel-talented ants is up to us. we are masters at not always wanting to follow the given tempo exactly and so we dance the forwards and backwards in our own rhythm, because we can. ‚again and again. time after time. the mosquito circles. nothing‘ is not a real haiku, but we know about the images meaning.

martin eugen raabenstein, 2024

more at kazukinakahara.com

01

Ein spöttisches, aber dennoch nachdenkliches Grinsen schimmert zwischen seinen Zeilen hindurch, wenn der Philosoph und Sinologe François Jullien sinniert, wie lange die europäische Kultur gereift sei, nur um sich selbst mit allerliebster Freude sogleich wieder zu hinterfragen und durch emsiges Abtragen der jahrhundertelang gefügten Fundamente zu zerlegen. In seinem Buch ‚China und die Psychoanalyse‘ ist der Übergang vom 19. zum 20. Jahrhundert sein reflektierter Höhepunkt, und die sogenannte kritische Geisteshaltung ist der Garant für den Wiederabstieg. Zu dieser Zeit beginnt sich das kolonialisierte Asien langsam wieder zu formen, und ausgerechnet der russisch-japanische Krieg 1904, in dem in der Moderne eine europäische Großmacht von Asiaten besiegt werden kann, inspiriert den jungen Mahatma Gandhi dazu, über Widerstand nachzudenken, wenn auch einen gewaltfreien. Mehr als ein Jahrhundert später stecken China und Japan wieder in ihren fest verwurzelten, historischen Stiefeln, während der geschichtsbefreite europäische Kontinent barfuß der kommenden Flut entgegenwimmert.

02

Das Tokugawa-Shogunat verfeinert in über 2 Jahrhunderten die auf unbedingten Regeln basierende japanische Kultur in der Edo-Zeit. Die Gesellschaft ist streng hierarchisch: Klasse, Familie, Individuum und Kunst, Literatur, Gartenbau – Alle und Alles begeht einen vorgezeichneten, nie zu verlassenden Weg. Wie sehr Sumi-e, Haiku und Karesansui in Form und Ausdruck höchste Präzision repräsentieren, sind sie doch gleichzeitig das Resultat einer totalen Staatskontrolle, eine durch eine unnachsichtige Autorität garantierte Ordnung. Persönlicher Freiraum ist in dieser feinmaschigen Regelstruktur nur in den Nischen, den kleinen Lücken zu finden. So entwickelt sich die Idee des MA, in dem die Leere als Freiraum, als Möglichkeit erwächst, im Gegensatz zum Konzept der Leere im Westen, die eine Dunkelheit, getragen von Verlust und Trauer, meint. Diese Leere findet sich auch in der freigelassenen Fläche, dem unbemalten Stück Papier, in dem der Gegensatz zwischen Form und Nicht-Form hinterfragt und in der Ausgewogenheit beider Elemente die Schönheit gesucht wird. Die Leere wird zu einer Verbindung, einem Spiel mit Zeit und Verlagerung.

03

Kazuki Nakahara dringt rhythmisch strukturierend in seine weiße Papierfläche ein. Seine zeichenformulierenden Spuren, zumeist mit Buntstift auf großflächige Japanpapierbögen aufgetragen, erobern die Leere wie Wasser. In konzeptionellen Skizzen vorbereitet, umfließen diese tanzenden Typographiebruchstücke die frei zu lassenden, weißen Inseln, um kurz vor Beendigung des Werkes von kräftigeren Kohlelinien blattüberspannend umgriffen, gehalten zu werden. Mit der räumlichen Entfernung vor dem Werk, in dem Zeichnung und Malerei sich vermählen, verliert die Schraffur des Details ihren Fokus und weicht einem samtigen, durch häufige Nutzung abgegriffen erscheinendem Gesamtbild. Entsprechend einer anderen, dem Zen-Buddhismus entspringenden Art, die Welt wahrzunehmen, ummantelt Nakaharas Kunst ebenso das Wabi Sabi, das Schlichte, Impermanente. Gleichwohl diese bedächtig gesetzten Kompositionen mit der Unbeständigkeit spielen, entsteht im Miteinander von Raum und Nicht-Raum ein zeitlicher Riss, indem etwas sehr Altes mit etwas sehr Neuem und Jungem in einen Dialog tritt.

04

Der nicht erst durch seinen Beitrag für die Royal Academy-Ausstellung ‚Sensing Spaces‘ im Westen bekannte Architekt und Visionär Kengo Kuma beschreibt eingehend, wie er die Leere in seiner Architektur, das MA, sucht. Das Projekt, so sagt er, ist dann erfolgreich, wenn es ihm gelingt, einen menschlichen, warmen und natürlichen Raum zu kreieren. Nachdem die japanische Wirtschaft nach 1991 schwächelt, verbleiben die Auftragsfelder des Architekten eher regional. Eine rege Zusammenarbeit mit lokalen Handwerkern entwickelt sich und damit eine für Kuma prägende Arbeitsgrundlage für zukünftige Bauten. Mit dem Projekt ‚The Exchange‘, 2019 in Sydney eröffnet, werden die Parallelen zu Nakaharas Vorgehen deutlich. Ein um das eigentliche Gebäude gewickeltes, hölzernes Band verschleiert Form und Funktion der darunterliegenden Architektur. Der unsichtbare Raum, verborgen hinter der täuschenden Oberfläche einer verspielten, um ihrer Unbeständigkeit wissenden Wirklichkeit, eröffnet die Einladung zum Tanz. Mit der Andeutung einer figurativen Lesbarkeit umweht Nakaharas Arbeiten die Idee, diese verlockende, angelehnte Tür zu öffnen, um in die Sonne zu treten.

05

Wenn es die Fassade ist, hinter die wir schauen sollen, der Strand, der unter dem Beton verborgen ruft, das Bild also, das wir betrachten, in uns einen Schalter umlegt, um so zu einer anderen, versteckten Wahrnehmung zu gelangen, sind wir entweder das Opfer unserer unstillbaren Unruhe, oder wir treiben willentlich und gelassen mit auf dem Fluss der unendlichen Wandlungen. Nakahara ist ein Meister handwerklicher Raumnahme. Im Spiel zwischen Nähe und Distanz, faktischer Darstellung und Abstraktion, oszilliert der Künstler zwischen dem Drama der realen Außenwelt und der selbstentzündlichen Reise ins Innere des Ich. Ob wir die Vergänglichkeit in einer abstrakten Fläche sehen wollen oder fein getriebene Wegesysteme tunnelbegabter Ameisen erahnen, liegt an uns. Wir sind Meister darin, nicht immer exakt dem vorgegebenen Tempo folgen zu wollen, und so tanzen wir den Vor- und Rückschritt in unserem eigenen Rhythmus, weil wir es können. ‚Wieder und wieder. Mal ums Mal. Umkreist die Mücke. Nichts.‘ ist kein echter Haiku, aber wir wissen, was das Bild meint.

martin eugen raabenstein, 2024

more at kazukinakahara.com

kazuki nakahara

kazuki nakahara

untitled, 160 x 88 cm

coloured pencil and charcoal on paper, 2022

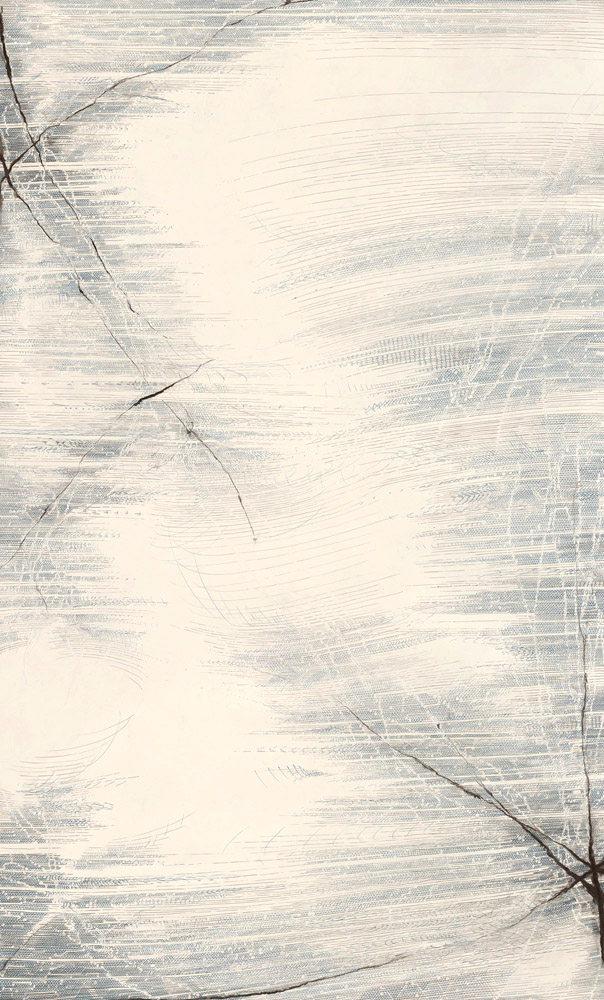

kazuki nakahara

untitled, 122 x 182 cm

coloured pencil and charcoal on paper, 2021

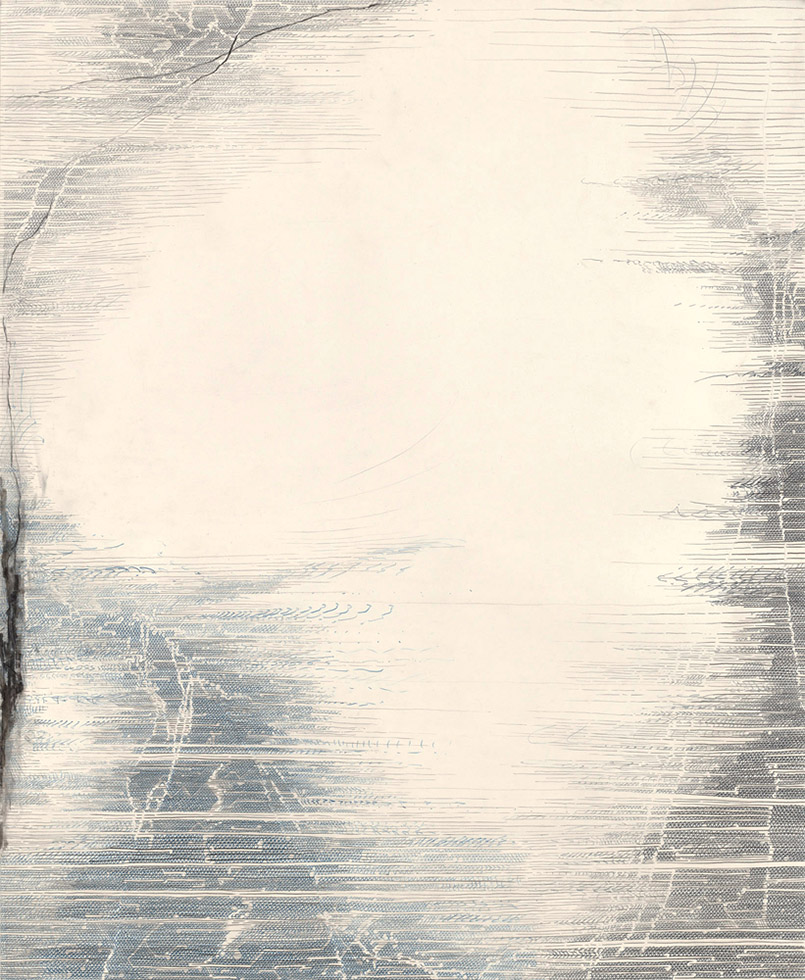

kazuki nakahara

untitled, 164 x 99 cm

coloured pencil and charcoal on paper, 2022

kazuki nakahara

untitled, 126 x 104 cm

coloured pencil and charcoal on paper, 2022

kazuki nakahara

01

a mocking yet thoughtful grin shimmers between his lines when the philosopher and sinologist françois jullien muses on how long european culture has matured, only to immediately question itself again with the greatest joy and to dismantle the foundations that have been laid for centuries. in his book ‚china and the psychoanalysis‘, the transition from the 19th to the 20th century is his reflected climax and the so-called critical mindset is the guarantee for the descent. at this time, colonized asia was slowly beginning to reshape itself, and the 1904 russo-japanese war, of all things, in which a great european power could be defeated by asians in modern times, inspired the young mahatma ghandi to ponder resistance, albeit a non-violent one. more than a century later, china and japan are back in their firmly rooted, historical boots, while the history-free european continent whimpers barefoot towards the coming tide.

02

for over two centuries, the tokugawa shogunate refined japanese culture in the edo period, which was based on absolute rules. society was strictly hierarchical, with class, family, the individual and art, literature, gardening, everyone and everything following a predetermined path that could never be abandoned. however much sumi-e, haiku and kasansui represent the highest precision in form and expression, they are at the same time the result of total state control, an order guaranteed by an implacable authority. in this fine-meshed regulatory structure, personal freedom can only be found in the niches, the small gaps, and thus the idea of MA develops, in which emptiness emerges as free space, as possibility, in contrast to the concept of emptiness in the west, which means a darkness borne of loss and mourning. this emptiness can also be found in the surface left free, the unpainted piece of paper, in which the contrast between form and non-form is questioned and beauty is sought in the balance of both elements. the emptiness becomes a connection, a play with time and displacement.

03

kazuki nakahara interfuses his white paper surface rhythmically and structurally, his traces of drawing, mostly applied with colored pencil on large sheets of japanese paper, conquer the empty space like water. prepared in conceptual sketches, these dancing fragments of typography flow around the white islands to be left free, only to be embraced and held by stronger charcoal lines spanning the sheet shortly before the work is completed. with the spatial distance in front of the work, in which drawing and painting merge, the hatching of the details loses its focus and gives way to a velvety overall picture that appears worn through frequent use. in accordance with another way of perceiving the world that stems from zen buddhism, nakahara’s art also envelops wabi sabi, the simple, impermanent. although these thoughtfully placed compositions play with impermanence, a temporal rift is created in the interaction of space and non-space, as something very old enters into a dialog with something very new and young.

04

the architect and visionary kengo kuma, known in the west not only for his contribution to the royal academy exhibition ’sensing spaces‘, describes in detail how he seeks the void in his architecture, the ma. the project, he says, is prosperous when he succeeds in creating a human, warm and natural space. with the japanese economy weakening after 1991, the architect’s commissions tended to remain regional. a lively collaboration with local craftsmen developed, providing kuma with a working basis for future buildings. the project ‚the exchange‘, which opened in sydney in 2019, clearly demonstrates the parallels to nakahara’s approach. a wooden band wrapped around the actual building disguises the form and function of the underlying architecture. the invisible space, concealed behind the deceptive surface of a playful reality, aware of its impermanence, opens the invitation to dance. with the suggestion of a figurative legibility, nakahara’s work is wrapped by the idea of opening this enticing, ajar door to step into the sun.

05

if it is the façade behind which we are supposed to look, the beach that calls out hidden beneath the concrete, the image we are looking at, that is, flips a switch in us in order to reach a different, hidden perception, we are either the victim of our insatiable restlessness, or we are willingly and calmly drifting along on the river of infinite change. nakahara is a master of the art of taking up space. in the play between proximity and distance, factual representation and abstraction, the artist oscillates between the drama of the real outside world and the inflammable journey into the inner self. whether we want to see transience in an abstract surface or sense the finely driven path systems of tunnel-talented ants is up to us. we are masters at not always wanting to follow the given tempo exactly and so we dance the forwards and backwards in our own rhythm, because we can. ‚again and again. time after time. the mosquito circles. nothing‘ is not a real haiku, but we know about the images meaning.

martin eugen raabenstein, 2024

more at kazukinakahara.com

01

Ein spöttisches, aber dennoch nachdenkliches Grinsen schimmert zwischen seinen Zeilen hindurch, wenn der Philosoph und Sinologe François Jullien sinniert, wie lange die europäische Kultur gereift sei, nur um sich selbst mit allerliebster Freude sogleich wieder zu hinterfragen und durch emsiges Abtragen der jahrhundertelang gefügten Fundamente zu zerlegen. In seinem Buch ‚China und die Psychoanalyse‘ ist der Übergang vom 19. zum 20. Jahrhundert sein reflektierter Höhepunkt, und die sogenannte kritische Geisteshaltung ist der Garant für den Wiederabstieg. Zu dieser Zeit beginnt sich das kolonialisierte Asien langsam wieder zu formen, und ausgerechnet der russisch-japanische Krieg 1904, in dem in der Moderne eine europäische Großmacht von Asiaten besiegt werden kann, inspiriert den jungen Mahatma Gandhi dazu, über Widerstand nachzudenken, wenn auch einen gewaltfreien. Mehr als ein Jahrhundert später stecken China und Japan wieder in ihren fest verwurzelten, historischen Stiefeln, während der geschichtsbefreite europäische Kontinent barfuß der kommenden Flut entgegenwimmert.

02

Das Tokugawa-Shogunat verfeinert in über 2 Jahrhunderten die auf unbedingten Regeln basierende japanische Kultur in der Edo-Zeit. Die Gesellschaft ist streng hierarchisch: Klasse, Familie, Individuum und Kunst, Literatur, Gartenbau – Alle und Alles begeht einen vorgezeichneten, nie zu verlassenden Weg. Wie sehr Sumi-e, Haiku und Kasansui in Form und Ausdruck höchste Präzision repräsentieren, sind sie doch gleichzeitig das Resultat einer totalen Staatskontrolle, eine durch eine unnachsichtige Autorität garantierte Ordnung. Persönlicher Freiraum ist in dieser feinmaschigen Regelstruktur nur in den Nischen, den kleinen Lücken zu finden. So entwickelt sich die Idee des MA, in dem die Leere als Freiraum, als Möglichkeit erwächst, im Gegensatz zum Konzept der Leere im Westen, die eine Dunkelheit, getragen von Verlust und Trauer, meint. Diese Leere findet sich auch in der freigelassenen Fläche, dem unbemalten Stück Papier, in dem der Gegensatz zwischen Form und Nicht-Form hinterfragt und in der Ausgewogenheit beider Elemente die Schönheit gesucht wird. Die Leere wird zu einer Verbindung, einem Spiel mit Zeit und Verlagerung.

03

Kazuki Nakahara dringt rhythmisch strukturierend in seine weiße Papierfläche ein. Seine zeichenformulierenden Spuren, zumeist mit Buntstift auf großflächige Japanpapierbögen aufgetragen, erobern die Leere wie Wasser. In konzeptionellen Skizzen vorbereitet, umfließen diese tanzenden Typographiebruchstücke die frei zu lassenden, weißen Inseln, um kurz vor Beendigung des Werkes von kräftigeren Kohlelinien blattüberspannend umgriffen, gehalten zu werden. Mit der räumlichen Entfernung vor dem Werk, in dem Zeichnung und Malerei sich vermählen, verliert die Schraffur des Details ihren Fokus und weicht einem samtigen, durch häufige Nutzung abgegriffen erscheinendem Gesamtbild. Entsprechend einer anderen, dem Zen-Buddhismus entspringenden Art, die Welt wahrzunehmen, ummantelt Nakaharas Kunst ebenso das Wabi Sabi, das Schlichte, Impermanente. Gleichwohl diese bedächtig gesetzten Kompositionen mit der Unbeständigkeit spielen, entsteht im Miteinander von Raum und Nicht-Raum ein zeitlicher Riss, indem etwas sehr Altes mit etwas sehr Neuem und Jungem in einen Dialog tritt.

04

Der nicht erst durch seinen Beitrag für die Royal Academy-Ausstellung ‚Sensing Spaces‘ im Westen bekannte Architekt und Visionär Kengo Kuma beschreibt eingehend, wie er die Leere in seiner Architektur, das MA, sucht. Das Projekt, so sagt er, ist dann erfolgreich, wenn es ihm gelingt, einen menschlichen, warmen und natürlichen Raum zu kreieren. Nachdem die japanische Wirtschaft nach 1991 schwächelt, verbleiben die Auftragsfelder des Architekten eher regional. Eine rege Zusammenarbeit mit lokalen Handwerkern entwickelt sich und damit eine für Kuma prägende Arbeitsgrundlage für zukünftige Bauten. Mit dem Projekt ‚The Exchange‘, 2019 in Sydney eröffnet, werden die Parallelen zu Nakaharas Vorgehen deutlich. Ein um das eigentliche Gebäude gewickeltes, hölzernes Band verschleiert Form und Funktion der darunterliegenden Architektur. Der unsichtbare Raum, verborgen hinter der täuschenden Oberfläche einer verspielten, um ihrer Unbeständigkeit wissenden Wirklichkeit, eröffnet die Einladung zum Tanz. Mit der Andeutung einer figurativen Lesbarkeit umweht Nakaharas Arbeiten die Idee, diese verlockende, angelehnte Tür zu öffnen, um in die Sonne zu treten.

05

Wenn es die Fassade ist, hinter die wir schauen sollen, der Strand, der unter dem Beton verborgen ruft, das Bild also, das wir betrachten, in uns einen Schalter umlegt, um so zu einer anderen, versteckten Wahrnehmung zu gelangen, sind wir entweder das Opfer unserer unstillbaren Unruhe, oder wir treiben willentlich und gelassen mit auf dem Fluss der unendlichen Wandlungen. Nakahara ist ein Meister handwerklicher Raumnahme. Im Spiel zwischen Nähe und Distanz, faktischer Darstellung und Abstraktion, oszilliert der Künstler zwischen dem Drama der realen Außenwelt und der selbstentzündlichen Reise ins Innere des Ich. Ob wir die Vergänglichkeit in einer abstrakten Fläche sehen wollen oder fein getriebene Wegesysteme tunnelbegabter Ameisen erahnen, liegt an uns. Wir sind Meister darin, nicht immer exakt dem vorgegebenen Tempo folgen zu wollen, und so tanzen wir den Vor- und Rückschritt in unserem eigenen Rhythmus, weil wir es können. ‚Wieder und wieder. Mal ums Mal. Umkreist die Mücke. Nichts.‘ ist kein echter Haiku, aber wir wissen, was das Bild meint.

martin eugen raabenstein, 2024

more at kazukinakahara.com

kazuki nakahara

kazuki nakahara

untitled, 160 x 88 cm

coloured pencil and charcoal on paper, 2022

kazuki nakahara

untitled, 122 x 182 cm

coloured pencil and charcoal on paper, 2021

kazuki nakahara

untitled, 164 x 99 cm

coloured pencil and charcoal on paper, 2022

kazuki nakahara

untitled, 126 x 104 cm

coloured pencil and charcoal on paper, 2022